Lullus, Raymundus [Ramon Llull] / Jac. Faber Stapulensis [Ed.] [sold]

[Opuscula] — Paris 1499

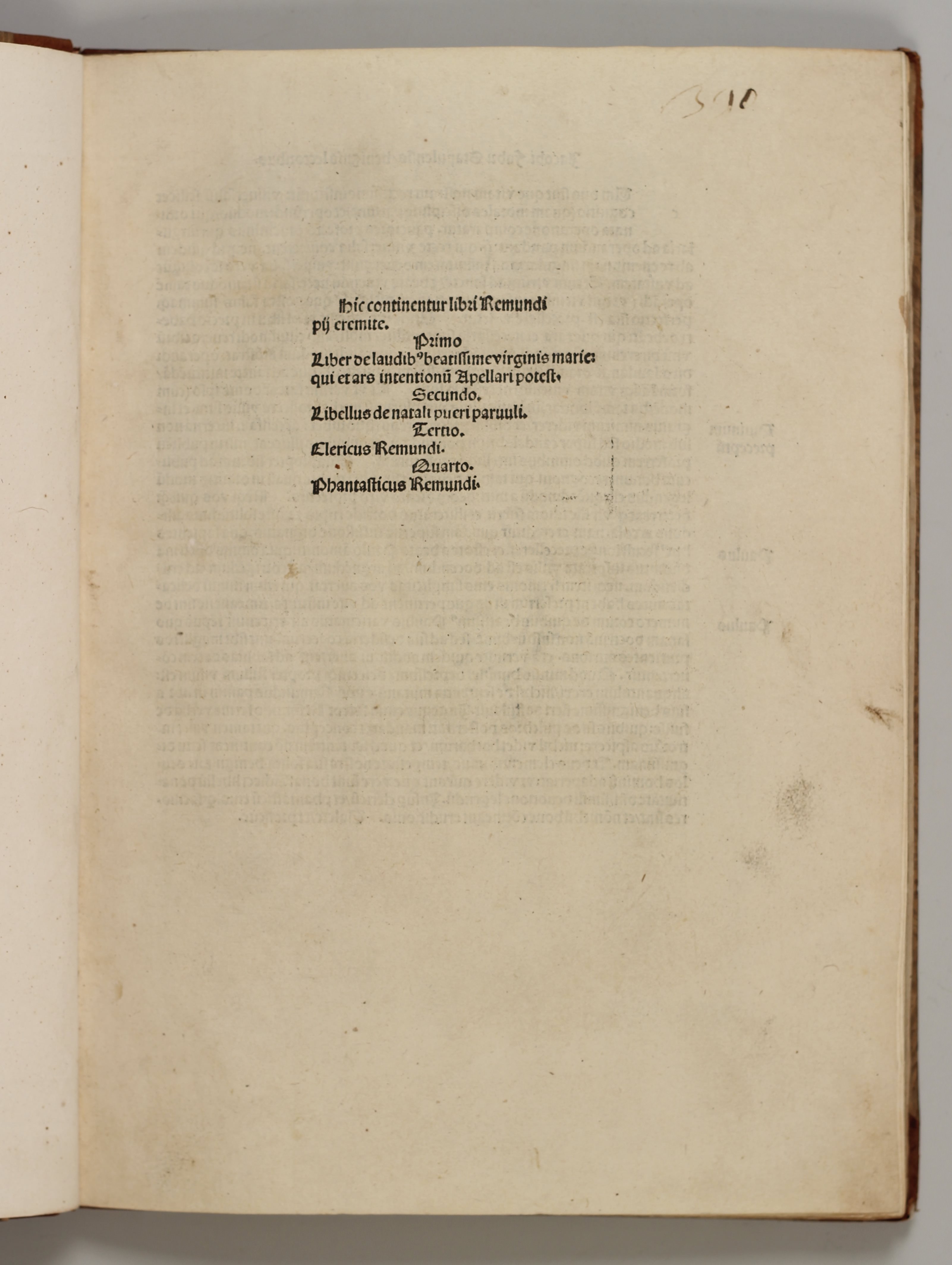

Hic continentur libri Remundi pij eremite

Primo

Liber de laudibus beatissime virginis marie: qui est ars intentionum apellari potest

Secundo

Libellus de natali pueri parvuli

Tertio

Clericus

Quarto

Phantasticus

[Colophon:] Impressum Parhisij per Guidonem Mercatorem: proprijs eiusdem sumptibus et expensis. Anno eiusdem domini salvatoris. 1499. 6. Aprilis.

[Paris, Guy Marchant, 6 April 1499]

First edition, first issue

Folio (275 x 198 mm). a-d8 e-g6 h8 i-m6 n4: ff. 85, (1) blank. A few early marginal markings in brown ink. Tear in upper blank margin of leaf K2. 19th century calf-backed boards, upper joint starting at bottom. A wide margined copy: a few leaves with lower deckle edges.

Rogent/Duran, Bibliografia de les impressions Lullianes, Barcelona 1927, I 20ff.

Rice, The prefatory epistles of Jacques Lefèvre d’Etaples and related texts, NY 1972, pp. 75ff.; ISTC il00390000.

„A man long born before his time.“1

De laudibus Mariae

Shortly before the first of the four texts assembled here was written, Llull had finished the Ars inventiva veritatis and the Ars amativa. Llull wrote these two works and the dialogue De Laudibus Mariae around 1290 at the court of his King of Aragón James II in Montpellier; the dialogue follows on from the two previous elaborations of the ars: „Verumtamen, in parte modum doctrinae Artis demonstrativae, inventivae et amativae procedendo tenemus“. (fol. 2v) It is discribed as „one of the most vivid and interesting dialogues of Ramòn Llull“ by Roger/Durant.

The subtitle added by Lefèvre „qui et ars intentionum apellari potest“ and the illustration on a1r make clear that the dialogue is not a devotional one, but a „Mariale in quaestiones difficiles“, in which, as the editors of the latest edition (Stuttgart 2005) write, the whole philosophy of Llull is reflected.

The „figura artis intentionum“ (2nd photo) represents the predications of Maria (the letter A); what is called intentio here is called dignitas or principium elsewhere in Llull’s work. The first nine intentiones (B-K) correspond to the dignitates of God in the ars inventiva veritatis, and also elsewhere in Llull’s work. With the added 21 further predicates of Mary, the number of the 30 chapters of the book is given.

The predicates here are called Intentiones, because in this way the essentially active, acting character of the qualities is to be expressed: for example, bonitas is not a substance resting in itself, but in it is thought to make something else good (bonificativum), as well as that which is capable of being made good (bonificabile), and the union of both in bonificare. Lohr2 stresses this side of the predicates: „His method of contemplation can … only be understood correctly if we take the dignities to stand for active powers.“

The conversations in the dialogue take place between the three allegorical female figures of Laus, Oratio and Intentio and a learned hermit; they have decided to go far away from the city; in the shade of a beautiful leafy tree near a clear and lovely spring (sub umbra cuiusdam frondentis arboris iuxta quendam fontem clarum et amenissimum … fol. a5v) they dispute about the nature and qualities of Mary; having succeeded in this, they decide to return to the cities, to the world, and to proclaim the insights and certainties they have gained: Completis sermonibus suis consenserunt in unum ut reverentur omnes in mundum. (f. 56v)

Liber natalis

This text, planned as a letter to King Philip of France around 1310 on Christmas Eve in Paris and written in January 1311, is also a dispute taking place in a loco amenissimo near Paris, here between the six ladies Laus, Oratio, Charitas, Contritio, Confessio and Satisfactio, to whom towards the end the divina bonitas, magnitudo, eternitas, potestas, intellectus, voluntas, virtus, gloria, perfectio, justicia and misericordia themselves speak. At the end Llull asks the King, the books and teachings of Averroes „expellere et de studio parisiensi extrahi et extirpare facere“. (f.66r).

On Faber’s principles of editing this text see P. Walter.3

Clericus

This was written by Llull in 1308 at Pisa. Since the original version is lost, Faber’s edition is the sole version we have. The book is aimed at the students of Paris University whose chancellor, dean and alijs primoribus Lull sent the book with the intention of reforming the education of future clerics.

Remarkable are the simple diagrams in the margin and below the respective chapter.

They may also have been in the lost manuscript Faber used. In any case they correspond to Faber’s preference to express relations graphically, be they logical or, like here, those of virtues and sins.

If one takes the illustrations to De acedia, the relationship between acedia, invidia and odium or between acedia, ira and desparatio is shown in the margin as an illustration. The lower scheme then brings both marginal schemes together into one.

At the end of the text, Llull addresses three requests to those responsible at the university.They are to ask the Pope and the Cardinals to set up four or five monasteries where the languages of the infidels (ydiomata infidelium) would be taught so that the Gospel could be proclaimed throughout the world; secondly, he asks that an army be raised to conquer the Holy Land, and thirdly, that a tithe be set up to be paid to the Church to finance these tasks.

Phantasticus

Also of this dialogue, written in 1311, the original version is lost, and Faber’s edition is the basis for subsequent editions.

On his way to Council of Vienne (1311) Lull meets a cleric. Together they continue their journey. As in the Clericus, Lull tells of his wish that the Pope and the Cardinals should set up language schools for future missionaries so that the Gospel could be proclaimed throughout the world; secondly, he would ask for the foundation of an order to remain in the Holy Land until all unbelievers are converted; and thirdly, the Pope and Cardinals should banish the heresies of Averroism (especially the doctrine of a double truth: a philosophical truth possibly contradictory to the theological truth) from the University of Paris. The cleric listens to this and calls Llull a „vir phantasticus“.

This and „doctor phantasticus“are the names Llull’s contrahents and scoffers liked to use – not surprising since Llull „left almost nothing of tradition untouched; he wanted to renew everything – Christianity, the coexistence of religions, logic and medicine, language, philosophy and theology …“ K. Flasch.4

For the editor of our edition, Lefèvre d’Étaples, Llull was not the „vir phantasticus“ but the „vir illuminatus“, an uneducated – which he wasn’t – medieval idiota speaking the word of God directly, „unvarnished by syllogistic reasoning“, a man of divine inspiration.

Lefèvre „discovered the foundation for his mystical theology and intuitive philosophy in the later medieval mystics, the writings of Dionysius the Areopagite and Nicholas of Cusa, and the thought of Ramón Lull.“ (Victor 514f.)5

In the paratext of his edition of Dionysius the Areopagite in 1499 Lefèvre calls the thought of Dionysius a „theologia vivificans“. The edition of Llull’s text starts a series of mystical writings, of „theologiae vivificantes“ published by Lefèvre; among the authors of these publishings are Hildegard of Bingen, Mechthild of Hackeborn, Hugo and Richard de S. Victore, Johannes Ruysbroeck, ps.-Dionysius of course, Johannes Damascenus, and Llull again, whose „Contemplationes“, the „Libellus Blaquerne de amico et amato“ and Proverbs, Lefèvre published in 1505 and 1516.

E. F. Rice summarizes Faber’s relationship to Llull and the theology and philosophy for which Llull stands: „Lefèvre was not himself a mystic. He recorded no visions for us; his mind apparently never deserted his flesh in ecstasy. But he found in the mystical tradition valuable examples of a Christian piety appropriate, in his view, to the needs and aspirations of his time: simple, clear, pure, eloquent, closely tied to scripture, unobscured by what he considered empty sophistry, morally instructive, warmly emotional. Mystical assumptions coloured his idea of liberty and influenced his theory of knowledge.“ (p. 103)6

––––––––––––––––––––––––––

1, 2 The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy, Cambridge 1988, pp. 543, 541

3 Peter Walter, J. Faber Stapulensis als Editor des Raimundus Lullus dargestellt am Beispiel des „Liber natalis puere parvuli Christi Jesu“, in: F. Dominguez e.a., Aristotelica et Lulliana magistro doct. Charles E. Lohr 70 annum …dedicata, The Hague 1995, pp. 545-559.

4 K. Flasch, Das philosophische Denken im Mittelalter, Stgt. 2000, p. 438

5 J. M. Victor, The Revival of Lullism at Paris, 1499-1516, in: Renaissance Quarterly, XXVIII (1975), pp. 504-534.

6 E. F. Rice, Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples and the medieval Christian mystics, in: Row/Stockdale (Eds.), Florilegium historiale. Essays presented to